I hate Roots.

I hate Roots.

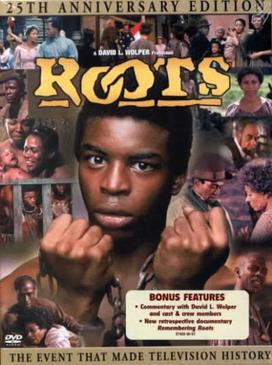

Never read the book, can barely watch more than 30 minutes of the mini-series, and have no intentions to expand my exposure any further. Granted, I have no personal beef with Alex Haley, and who doesn’t love LeVar (Geordi!) Burton? In fact, I offer a respectful nod to the effort it took to even get it slotted on to major network programming (apparently, SOMEBODY called in a few favors that year). But nonetheless, unapologetically, I’ll pass.

Why?

Because in a way, I’ve already read the book. Already seen the movie before. I’ve been exposed to this kind of content, and it pretty much hits me like cold oatmeal (that is, I’m willing to accept it if nothing else is around, but damned if there aren’t better options for my palate). The tale is just all too familiar: noble Black man/woman/child protagonist (sometimes a combination of the three) courageously trudges through the muck and mire of unspeakably cruel acts, spurred by bigotry and ignorance affixed to various unsavory points in human history. Somehow this person (usually) manages to overcome at least some of these atrocities en route to some point of affirmation that he/she/they are worthy of more than the inhumanity they’ve endured from myriad social forces conspiring against their very existence, and ultimately we the audience are asked/expected to walk away with some kernel of insight into, or at least a basic acceptance of the relevance of Blackness (be it in this country or abroad) to our existence, and why we should “never, ever forget…”

Sound familiar?

Now, far be it from me to begrudge anyone the right or outlet to tell a story or have a story about themselves told. Especially if it carries even an inkling of resonance to someone else’s reality. After all, we bipeds do like our stories. All I’m saying is the “Woe is me/We shall overcome” version of the story of Black people has been told and retold. And then rewritten and retold again. And again. Yes — sometimes the stories are well-written. And yes, sometimes they’re even fairly authentic to historical accounts of the Black experience.

But all the while, with the passing of each minute of those excruciating 30, I can’t help but think:

I get it.

Really.

I f*cking GET IT.

The history of Black people is a painful one. Few rational beings would deny that. Irrespective of whatever box we check off under “race,” most of us acknowledge that Black people have endured great horrors over the expanse of recorded history. Similarly, we are cognizant that the Black experience is still fraught with many hardships today: poverty, mass incarceration, broken families, disassociation from legitimate means of goal attainment, pervasive and ongoing institutional inequality. All of this eventually comes to light in the documentation and summation of historical and present-day accounts of Blackness. But that said, in poking around through such accounts like so many ashes and embers remaining from a once-roaring flame, I ponder: Where to from here? In studying, recording, presenting and interpreting the trials and “tribble-lations” (woot — STAR TREK WEEK!) of Black people and Blackness conceptually, again I ponder: Where to from here?

While respectfully acknowledging what Blackness has been and currently is, what are we to say of the future? Who will we (Black people) be? What will we dream? What will we fear? Who (if anyone) will fear us, and conversely who or what will inspire dread within us? What will our relevance be? By and large, answers to such lofty inquiries — even wildly speculative ones — are offered from a scant selection of sources. Thankfully, for Black nerds like myself, there is sci-fi. Sweet, glorious, sci-fi.

To begin, let’s first agree that science fiction is uniquely poised to spark our collective consciousness and imagination by presenting visions of how past and current realities might be re-imagined within the context of a not-yet-existent, but conceivable future. Let us also agree that science fiction should be held loosely as fiction given its propensity to pull from the real in order to paint a picture of the seemingly unreal. Bearing these agreements, I maintain that Star Trek is classic sci-fi in that it is as much about speculation as to what the future may hold based upon what has been — and what currently is “being” — as it is about actual storytelling. Evidenced from the very TOS beginnings of Kirk and his intrepid cornucopia of a crew, Gene Roddenberry was intent on carefully juggling the imperatives of fanciful storytelling — he, ever the playful raconteur — and acerbic social commentary. It is the latter that I draw attention to, as Star Trek is among those few aforementioned sources that offer a chance to address this composition’s central focus with some measure of sophistication.

Throughout the 47 years of Star Trek set before us, its creators have been challenging us all along the way to consider any number of social realities upon which human existence is defined. Gender roles, racism, love, honor, loyalty, family, justice, sexuality… so many questions and prognostications surrounding such concepts have been placed before us like some bouquet of social discourse. Turning to the question at present, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine seems to offer us the only compelling answer to that question. Whereas Roots and material of its ilk may be adept at addressing where Blackness has come from and where it is now, it falls ever short of addressing where Blackness can go, or what it can become. For that future perspective, dear reader, I humbly submit you must turn to DS9’s Captain Benjamin Sisko, and in particular two episodes of the seminal series demonstrative of the new challenge to re-imagine our notions of Blackness.

The measure of a man — any man, let alone a Black man — is to be able to examine oneself critically without fear of consequence when circumstances warrant the effort. This is precisely what Sisko must do in this episode. Emotionally wounded and frustrated from dutifully posting rosters of casualties of the Federation/Dominion War, Sisko is revealed to be an honorable man, but also a desperate one. Conflicted between his own honor and a decidedly dishonorable act that nonetheless could hasten defeat of the Dominion, thus ending the War and staving further loss of life, Sisko spirals down a series of actions — each of equally dubious morality. Collaboration with Cardassian spies and known criminals, fabricating evidence, bribery, lying, intimidation, all the while compromising numerous DS9 and Federation protocols, and ultimately sacrificing Romulan lives to aid Federation and allied forces. Confronting these decisions via his personal station log reveals to us a version of Sisko that is startlingly imperfect. He is profoundly flawed and prone to error in judgment. But just as importantly, he is willing — even compelled — to acknowledge his flaws.

Faced with a situation for which steering a completely moral course of action would be seemingly impossible, it becomes clear that Sisko can neither make completely right nor completely wrong choices…only choices devoid of such clarity. It is critical for us to see Sisko struggling with these decisions because ultimately it reminds us of his base fallibility. That is to say, before Sisko is a Black man, he is first a man, and even before that, human and thus inherently flawed. But what is even more profound and important to take away from this presentation of Sisko is that it is an honest depiction of both what it is to be human and to be Black. His moral dilemma transcends race. His actions, questionable as they are, could be those of any other captain confronted with the same circumstances. But in our construction of historic and present perceptions of Blackness, these qualities are rarely shown. Self-doubt. Humility. Honesty. Resolve.

In “Waltz,” we find Sisko and former Cardassian prefect to Bajor, Dukat, stranded on an uncharted planet en route to Dukat’s initial hearing for war crimes committed both by and under him during the Cardassian occupation. How they’ve ended up stranded on the planet is of little importance, but the ensuing debate that takes place between them is. Amidst Dukat’s rants of benevolence towards the Bajorans, his claims of ungratefulness from them in return (note: Dukat is quite insane at this point in the DS9 arc), and Sisko careful retorts, it would seem that Sisko’s rebuttals are informed at least in part from a deep connection with the painful knowledge of his own ancestral history and the uncanny similarities with what Dukat subjected the Bajorans to. A particular exchange between the two illustrates:

Sisko: Why do you think [the Bajorans] didn’t appreciate this rare opportunity you were offering them?

Dukat: Because they were blind, ignorant fools. If only they had cooperated with us, we could have turned their world into a paradise. From the moment we arrived on Bajor, it was clear that we were the superior race. But they couldn’t accept that. They wanted to be treated as equal, when they most certainly were not. We did not choose to be the superior race; fate handed us that role.

It’s a subtle implication, but one made fairly obvious upon studying the Sisko narrative over the previous five seasons. Sisko knows the pains of his own ancestors, and can recognize the similarity between Dukat’s justifications and those under which slavery, Jim Crow, and apartheid were upheld. Sisko is deeply defined by his ancestral ties as he draws strength and wisdom from them. It is Sisko’s firm Blackness and keen awareness of his own people’s history that allows him to immediately recognize Dukat’s bold claims as little more than the desperate, ramblings of a delusional former despot seeking vengeance upon a people who ultimately fought against subjugation and human indignity much the way Sisko’s own Black forefathers had. Retroactively drawing upon the past to inform the present and strategize a forward plan (in this case, the forward plan being the eventual elimination of Dukat). This is a key quality of Blackness that rarely (if ever) sees light.

Though battered, bruised, and barely nourished off of mostly water and soup rations, this episode also reveals a trait of Sisko’s not necessarily forefront in the profiling of the character: supreme intellect. Granted, he’s not the only smarty-pants amongst the cast of characters, but it is important that he is clearly among the sharpest minds woven into the DS9 tapestry. And that he is Black, for it directly challenges long-standing perspectives (and one embarrassingly supported at times within my own milieu of academia (you’d think our asses would know better) of the intellectual inferiority of Black people.

Though battered, bruised, and barely nourished off of mostly water and soup rations, this episode also reveals a trait of Sisko’s not necessarily forefront in the profiling of the character: supreme intellect. Granted, he’s not the only smarty-pants amongst the cast of characters, but it is important that he is clearly among the sharpest minds woven into the DS9 tapestry. And that he is Black, for it directly challenges long-standing perspectives (and one embarrassingly supported at times within my own milieu of academia (you’d think our asses would know better) of the intellectual inferiority of Black people.

To conclude, in Captain Sisko, we are given a man. A Black man, commanding in presence, but gentle and careful in wielding that presence with grace and tact. In that presentation, we are offered a vision of Blackness far afield of what is available to us at present. Shattered are the visages of the poor and downtrodden, the violated, the incarcerated, the uneducated, the degenerate preying upon society, the father unwilling and/or incapable of accepting the profound privilege of parenthood, the young person prone to deviance, the adult destined to criminality, the jobless, the meekly resigned to failure and the hopelessly distant from all that society has and offers to those fortunate enough not to be associated with Blackness. Left standing upon those broken remnants of such distasteful associations is this new Blackness in the form of a proud man who dutifully upholds his oath to a federation he has vowed allegiance to, and moreover, a set of ideals endemic to his very essence despite the loss of a great love and legitimate questions about the integrity of that same federation he defends. Left standing is a man who masterfully commands both a port of call in arguably the busiest section of currently charted space, and less arguably one of the most powerful Federation gunships ever devised.

And looking up at the precipice where he stands… is us. Not just we nerds of color. Not just nerds in general. Or people of color. It is us. All of us. Now that we’ve been given this image, what can we do with it? I contend that with so many contemporary notions of Blackness so effectively crushed under the weight of “The Sisko,” we must begin to consider more seriously Blackness beyond where it has been and where it is today.

Do we dare dream of a Sisko? Do we dare dream of an era of human existence where Blackness as embodied in such a man is possible?

Dream, dear reader, dream. And once you’ve awaken from that dream, do.

For only then can a tangible future unfold where a Sisko is no longer merely dreamt…

You are the dreamer… *and* the dream. 😉